Nas was wrong. Hip-hop is not dead.

No, it’s in a hospital bed. It’s been shot three times, and the beeping noise from the heart monitor by its bedside is growing more frequent by the minute. Its situation is critical.

The first shot was from the cliché topics: Partying, smoking weed, making money, and former relationships. Essentially Wiz Khalifa’s entire discography.

The second was the disappearance of basic poetic elements. The disappearance of lyricism, rhyme scheme, and ‘flow.’ Look at ‘rappers’ like Lil’ Wayne, with his nails-on-a-chalkboard voice, croaking incoherent statements like “Young Tunchi baaaaaby” repeatedly.

The third was the lack of respect for hip-hop as an art. Hipsters would call it the shift to the mainstream: massive labels simply trying to maximize profits, while, in turn, minimizing creativity.

Though on the edge of oblivion, a potential savior stuck his foot in the door of the hospital room at the end of last month.

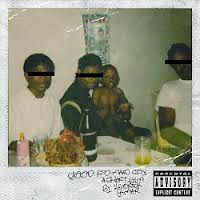

Mostly unnoticed outside of underground and alternative circles for the past three years, Compton MC Kendrick Lamar dropped his debut studio album “good kid, m.A.A.d city” to unprecedented critical acclaim.

A beautiful offering, it tells the story of a 17-year-old Lamar over a 24-hour period in one of America’s most infamous cities. Old school beats, incredible flow, impressive lyricism, and masterful story-telling make the album an instant classic.

However, what makes the album, and Lamar, most impressive is the return to the lost days of hip-hop as an art, while simultaneously appealing to the Lil’ Wayne-loving mainstream.

Lamar is the foil to the three aforementioned threats to hip-hop’s existence. While he does delve into typical topics, he gives a fascinating view from across the aisle. On “Section 80,” his debut EP released exclusively on iTunes, Lamar discussed the problems and negative influences alcohol and drugs have on the youth of America today.

On “good kid, m.A.A.d. City,” this theme is also prevalent. Lamar discusses the gang-banging, party lifestyle, but from his pressured perspective, one that did not wish to be part of the status quo. “The Art of Peer Pressure” captures this beautifully. “Normally i’m a peacemaker, but I’m with the homies right now.”

It’s refreshing to hear about social issues again: a Tupac-esque view of the world the majority of us see, not the posh parties that only the music industry elite experience. While visited in the 2000s, none feel as credible as Lamar’s.

Perhaps Lamar’s strongest suit is his poetic ability. Best illustrating this is “Sing About me, I’m Dying of Thirst” in which Lamar discusses Compton life from three different viewpoints. He begins by talking from the perspective of his friend Dave’s brother, following Dave’s death.

Complex rhyme scheme is present, constantly changing to fit the tone of the song and perspective. This has become rare in mainstream hip-hop today by way of focus on catchy choruses and focus on the sound of the song.

Flow is also at a high level in each of Lamar’s songs, but is at its highest level on his song “Rigamortis” off of “Section 80.” Lamar weaves across his verses without a single break in cadence. This is in complete contrast to Lil’ Wayne, or even recent Eminem, who feel that they can rhyme, but do so with abrupt breaks and pauses. For Lil’ Wayne, the breaks mean his trademark squawking, and with Eminem, the breaks mean more yelling.

Lamar also shows reverence to the art which he contributes to. This could immediately be seen with the release of “good kid, m.A.A.d. City” and critical response calling it a classic.

“It’s classic-worthy right now. It will be a classic,” Lamar said to US Rap News recently. “Ain’t nothing missing from it to be a classic. It just takes time.”

He demonstrates unusual patience and respect in a genre today full of rappers claiming to be the “best rapper alive.” I’m talking about you again, Lil Wayne.

There’s not much left to say. Welcome the newly crowned king of Compton, and this generation’s savior of hip-hop: Kendrick Lamar.